The land of We/2 - The void left by the decline of the Grain Banks

by Luigino Bruni

published in Avvenire on 30/09/2023

The policy of central governments, first the Bourbons and then the Piedmontese, with the intention of taking control of the agricultural credit institutions from the Church, caused a lot of damage to the South and to small villages

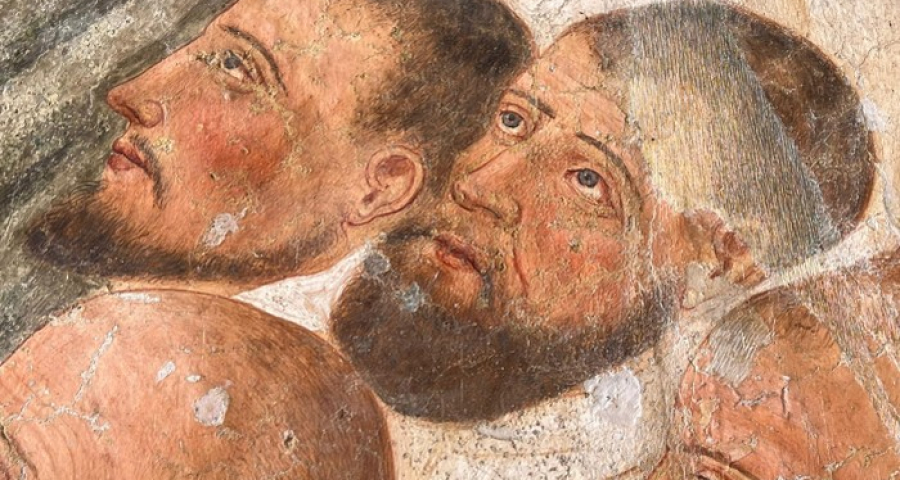

Along with some dark pages, the age of the Counter-Reformation has also seen some luminous ones. Because the ‘land of We’ is the land of community, and community is always an interweaving of light and shadow. One of the luminous pages is that written by the Capuchins, by the Bishops and by many Christians who gave life to the hundreds of Monti di Pietà (Pawn shops) and Monti Frumentari (Grain Banks), and decidedly took the side of the poorest people, especially in Southern Italy. They are pages as luminous as they are unknown and untold by the Social Doctrine of the Church itself, which was formally born in 1891 (Rerum Novarum) when the Monti (Banks) were already in decline and systematically neglected them. And so we do not know that the 114 Monti Frumentari of the Venetian Republic at the end of the 18th century "will be replaced by the rural coffers desired by Leone Wollemborg" (Paola Avallone, Alle origini del credito agrario, 2014, p. 85). However, this transformation of the Monti worked partly in the North, less so in the Centre and essentially failed in Southern Italy, where the void left by the Monti remained empty. Let's see why.

In the history of the Grain Banks there is a specific Southern Question, which begins with the Bourbons and continues with the unitary State. In the Kingdom of Naples, the Grain Banks developed thanks to the significant impulse given by the Church, both institutional (Bishops) and charismatic (Capuchins). A key figure was the Dominican Bishop, Pierfrancesco Orsini (Gravina 1650, Rome 1730), the future Pope Benedict XIII. In Manfredonia (Siponto), where he was Bishop, he established his first Monte Frumentario in 1678 and when he became bishop of Benevento, he established a Monte Frumentario there in 1686 and caused at least one to be established in each village and city leading to the establishment of over a hundred. When he became Pope, he encouraged their establishment everywhere.

It is precisely around the role of the Church in the management of the Monti that the decisive games of their history in Southern Italy were played out. In fact, in 1741, there was a Concordat between the Bourbons and Pope Benedict XIV, which led to the secularization of the Grain Banks, to lessen the interference of the Church in the economic life of the cities. What were the results? A few decades later, Francesco Longano, economist and assistant philosopher to the chair of Antonio Genovesi, wrote very clear and important words in his report following a trip to Molise (and Foggia),: "From time immemorial, for the public relief of the people, a large multitude of Monti di Pietà [Monti frumentari] or Luoghi Pii was found in each Province of the Kingdom. They were so subject to the Bishops and their administration was so exact, that they had prospered immensely. Their income mostly consisted of grain, but also cattle, sheep, and cash rents. An excessive vigilance which in a very short time, together with the annual administrators, reduced, exploited and impoverished them all. Eight or ten privileged people, poor or rich, have formed a kind of monopoly. The rich out of greed, the poor plunder out of need" (Viaggio dell' abate Longano per la Capitanata, 1790, pp. 188-189). The operation of the Bourbons had therefore produced "the irreparable loss of a work of extreme public utility in almost every city, land and village of the Province" (p. 259). And therefore Longano concluded: "We immediately understand the need to re-establish them, by declaring them to be ecclesiastical goods again and subject to the Bishops' Direction" (p. 260). This was a counter-reform which never happened.

As the historian Paola Avallone recalls, "the Grain Banks enjoyed a certain flourishing as long as they were free to operate according to the statutes they had given themselves and as long as they were managed locally by people appointed by the parish priest and held to account for their management to the episcopal authority, as indicated by Pope Benedict XIII after 1724. They prospered as long as they managed to adapt to the needs of the local community “(cit., p. 24). The policy of the central governments, first the Bourbons and then the Piedmontese, with the intention of taking control of the Monti away from the Church, caused a lot of damage, in particular in the South, where the Church had carried out many civil and economic functions for centuries, especially in small villages and among the poorest. They wanted to centralize the management of the Monti, not recognizing their fragile but essential local and community structure, and they caused them to die.

Emblematic in this regard is the failure of the ‘General Grain Bank of the Kingdom of Naples, a central mega-institution (based in Foggia), which should have managed all the Monti scattered throughout the kingdom as peripheral branches, also to overcome the plague of the infamous ‘oral contracts’ in the countryside. Founded in 1781, it never took off. The bureaucracy increased, the distance between those who governed the Monti and the poor farmers increased, and attempts were made to separate the financial component from the charitable one, undermining that dual nature that instead constituted the soul and the secret of their success. It was therefore an anti-subsidiary reform, reinforced by the post-revolutionary French period, by the restoration and finally by the unitary State which tried to transform the Monti into ‘agricultural loan banks’ or ‘savings banks‘, institutions far from the tradition of the villages of the South, from the spirit of those places. I traced two royal decrees, from 31.1.1878 and 14.7.1889, which respectively transformed "the two Monti Frumentari and the pecuniary bank of Roccanova (PZ), and invested their assets in favour of the Loans e Savings Bank", and "the Monti Frumentari of Maltignano (AP) in an Agricultural Loan Bank". The verb used by the bureaucrat of the decree, ‘invert’, resonates today as a prophetic verb: it was precisely a reversal of the meaning of the Monti that was generated by laws that did not understand them. From the decrees we read that in the small Lucanian municipality of Roccanova there were three Monti, and in the village of Maltignano the term ‘Monti’ is used in the plural, testifying how much those blessed institutions were widespread and capillary. In addition, "the maneuver of transforming the Monti Frumentari into Loan Banks, through the conversion of grain into money, particularly favoured the classes not directly interested in the work of the fields... Usury ended up with having the upper hand" (Michele Valente, "Evoluzione socioeconomica dei Sassi di Matera nel XX secolo", 2021, p. 29).

The transformation of the Monti into these new ‘Northern’ coffers therefore involved a financialisation of the Monti Frumentari which, unlike the Monti Pecuniari that often accompanied them, used grain as currency. The great innovation of those different banks was the use of grain as currency; the novelty was precisely the reduction of an intermediary step, a crucial element in a world with very little money and therefore held by usurers. The new laws forced the Monti to abandon grain-currency and transform themselves into ordinary financial institutions. And there they died. Moreover, the laws of the State did not understand the hybrid nature of these institutions, credit and charity, contract and gift and fought it, without understanding that opposing this hybrid nature meant denying the history of the Monti, who lived as long as and as long as they were spurious, mixed and contaminated. They wanted to separate what was united by nature and vocation, and they made them die. Of course, we all know that behind a mass extinction of thousands of Monti there are many reasons inscribed in the evolution of Italian and European society over the centuries, but the anti-subsidiarity reforms, the anti-clerical ideological attitude, the cultural distance between the new rulers and the farmers, were decisive elements for this economic and social massacre: who knows what southern finance, economy and society could have been if the Monti had been understood and protected? Giustino Fortunato, a southern politician and intellectual, was very opposed to the reform of the Monti and in general to the agrarian and economic policy of the unitary State in the South. In a letter to Pasquale Villari dated 18.1.1878, he wrote: "A reform made in depth on preconceived ideas, on a priori... The confusion is great. First example: the transformation of the Monti Frumentari into Agricultural Loan Funds" (Carteggio (1865-1911), pp. 11-12). The reform was, for Fortunato, a true "gravestone" for the Monti and for the “cafoni” (ignorant peasants).

And here we must return to the vocation and nature of the ‘Catholic’ and meridian economy. The pastoral action of the Counter-Reformation had strengthened and developed the widespread presence of the Church in the countryside, which, especially in the South, was in a condition of serious degradation, including economic deterioration. The constant presence of friars, nuns and priests in every village, in the parishes, in the many rural convents, had led the Church to understand the real needs of real people, and so it became expert in concrete poverty and the economy. And the Monti Frumentari were born: "As long as those institutions were administered by ecclesiastics, the goods kept in them were considered sacrosanct and therefore untouchable. From the moment they were secularized, they were plundered without any restraint (Paola Avallone, cit., p. 27).

What still remains in Italy and in southern Europe of the social and civil tradition, of the institutions of financial solidarity, today risks suffering the same fate as the Monti Frumentari, where the rulers are no longer the Bourbons and the Piedmontese but the algorithms of Basel and of the national and international financial institutions, which separate credit from communities, which distance choices from regions, which no longer listen to the real needs of concrete people and when they try to listen to them they do not understand them because they speak too different languages, and without translators.

I end by giving the floor to Ignazio Silone, who has redeemed the honour of the word ‘cafoni’, a word too full of injustice, pain and hope, which still awaits the day when pain will no longer be a shame: "I well know that the term of ‘cafone’, in the current language of my country, is a term of offence and mockery: but I use it in this book in the certainty that when in my country pain will no longer be a shame, it will become a name of respect, and perhaps even of honour" (Fontamara, Introduction).