The land of We/1 - The origin and meaning of the “Monti frumentari (Grain Banks)”

by Luigino Bruni

published in Avvenire on 23/09/2023

The Franciscans, and then the Church and society, understood that when dealing with poverty and the scarcity of money, there is a simple solution which is often forgotten: to reduce the use of money. The modern Catholic and meridian world has generated its own idea of economy, different in many aspects from that of Nordic and Protestant capitalism. The reaction of the Church of Rome to the Lutheran schism strengthened and amplified some dimensions of the market and finance already present in the Middle Ages and created new ones. In the series "The land of We", Luigino Bruni continues his reflection on the origins and roots of capitalism and society in the age of the Counter-Reformation.

The fight against usury is one of the constant features in the history of the pre-modern Church. Bishops and monks, who were close to the people, understood that the first victims of usury were above all the poorest. In over a thousand years, between the Council of Elvira (about 305) and that of Vienna (1311), there were about "seventy councils in every district" which used very strong words against usury (P.G. Gaggia, Le usure, p. 3). And while Popes and Bishops issued decrees and documents against usury, Bishops and charisms set up anti-usury financial institutions, so that the proclamation of documents did not remain abstract. In the Church, reality has always been superior to the idea, ever since the logos decided to become a child. This tenacious fight against usury and these anti-Usury institutions is part of the very roots of Europe. They include the Franciscan Monti di Pietà (pawn shops) which were very important, and which for some decades now have finally become the focus of renewed interest. Less studied are the Monti Frumentari (Grain Banks), also of Franciscan inspiration. But how much should we thank Francis and his followers? Hybrid institutions, just as "the Catholic economy", was (and is), the communitarian and Latin economy, that "land of We" that assimilated its mix, its ambivalence, its flesh and its blood from the community.

Like the Monti di Pietà, the Monti Frumentari were partly bank, partly assistance, partly loan, partly gift, partly market, partly solidarity, gratuity and interest, individual and community, honesty and corruption, trust and surety, city and church. The Grain Banks were a fundamental institution for the Italian rural economy (and beyond), especially that of the Centre-South, and they remained so for over four centuries (!). And like the Monti di Pietà, the Monti Frumentari also came into being in imitation of pre-existing institutions. For the Montes pietatis, the Franciscans of the Observance were inspired by the Roman deposita pietatis (pietas was also a great Roman word) and also the ecclesiastics of the first centuries, institutions that were "piety’s deposit fund (…) to support (…) poor people (...) such too, as have suffered shipwreck" (Tertullian, Apol. 39.6). But certainly the Franciscans imitated above all the Jewish "pawnshops", bringing innovations: low interest, the type of pawn, the timing of repayments... The Grain Banks (or granary, wheat, nummari, abundance, relief, flour, chestnuts banks ...) were born as a development of public grain and seed deposits, managed in the Middle Ages by municipalities or monasteries to cope with bad harvests and famines. In Massa Marittima the "Palace of Abundance" dates back to 1265. The name of the municipality of Montegranaro refers to medieval (perhaps Roman) public deposits of wheat, barley and cereals. The first icons of banks were mountains, think of the Chigi bankers, to tell us that the mountain, the deposit, and piling-up, were the first form of modern finance.

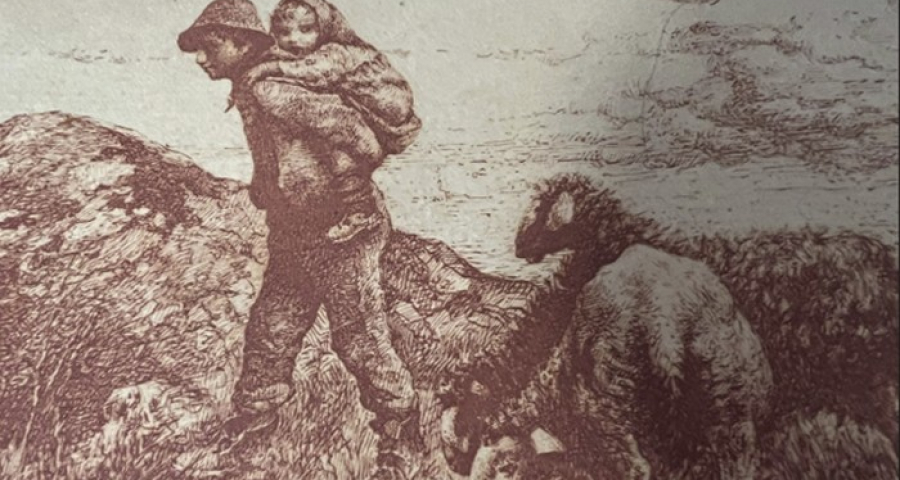

Wheat was the first name of the Mediterranean economy (F. Braudel). It was central for the life of mostly rural populations, in trade, for the wealth and poverty of cities, fiefdoms, countryside; and it took a war in Europe to remind us that we still live and die for wheat. The Bible can also be told as a story of grain and bread: from manna to the Eucharist. The Grain Banks were the realization of Joseph's wisdom, of his ability to interpret dreams and thus to cope with the years of "lean cows" by accumulating grain deposits during the "fat cows". This is one of the most sad and beautiful stories about betrayed and cared for brotherhood and it is accompanied by the smell of wheat, which is the same smell as in the story of Ruth, the ancestor of Jesus. Tithing and gleaning were institutions of solidarity with nature, typical of a non-monetary and predominantly agricultural world. The Temple of Jerusalem itself, and before it the sanctuaries, also carried out the function of collecting, preserving and redistributing seeds.

The Franciscans turned the old wheat banks into something new and created the Monti Frumentari (Grain Banks). When they visited the people of the rural villages, they listened to their aspirations and realized that the small and medium peasant (sharecropper or emphyteuta) was often in great difficulty: all it took was a poor year, an accident, a disease or a flood and the grain destined for seed for the next year was consumed so as not to die of hunger and so for the new sowing they had to go into debt, usually with usurers who drove them into poverty. The Grain Banks were born in the same places as the Monti di Pietà, but with distinct statutes and officials. They were not purely philanthropic entities: a non-monetary "interest" was paid on the grain. In general, the bushel was taken "by the level" and returned "by the heap"; a small interest therefore, not too different from the monetary rate of the Monti di Pietà (around 5%) – the Franciscans did not think that gratuity coincided with free. The work of Bernardino da Feltre was fundamental because in 1515 a papal bull (Inter multiplices, Leo X) recognized the lawfulness of the interest of the Monti di Pietà. The first Franciscan Grain Banks came into being in the 1480s, between Umbria and Abruzzo. The names of these first Monti, "Monte della Pietà del grano della Vergine Maria" of Rieti, or "Monte della Pietà del grano" of Sulmona, reveal an initial budding of the Grain Banks from the Monti di Pietà. The Franciscans understood that in the rural context monetary lending did not work, and they imagined non-monetary banks. Wheat was in fact decisive in the life and death of people and in a world with very little currency in circulation, those who held the money had too great a power not to abuse it through usury. Later, the Monti Pecuniari (which always lent wheat and agricultural products but for payment in cash) were added to the Grain Banks but the use of wheat as currency (the "grain") was the great innovation of the Monti and the reason for their longevity.

To date, it seems that the oldest Monte is that of Norcia (1487), founded by Fr. Andrea da Faenza (the true wheat missionary). However, it is interesting that, in 1771, the historian A.L. Antinori claimed the primacy of Leonessa: "In 1446, under the care of Antonio di Colandrea, the Monti di Pietà in Lagonessa built a strong room for deposits and pawns near the square" (cf. Giuseppe Chiaretti, Leonessa Arte, History, Tourism, 1995). The stone, an entrance portal, is preserved today in the local convent of St. Frances. The payment of interest to the Grain Bank was easier for the Church to accept, because the ethical issue of usury depended on the ancient thesis of the sterility of money, a sterility that does not exist in wheat: here the interest (or increase) was considered a sharing of the natural profit resulting from the generosity of the land (sow 1 and reap 10).

The historian, Palmerino Savoia, tells us about Bishop Orsini’s incessant work to establish Grain Banks at the end of the seventeenth century. Orsini was the future Pope Benedict XIII, known as "God's farmer" (to whom we will return). Savoia described the operation of the Grain Bank of Benevento in this way: "The Monte was administered by two governors and two custodians who held office for one year and were appointed by the Archbishop. The loan of the grain was made four times a year: in October to help with sowing, in December to help the needy during the Christmas holidays, in March for the Easter holidays and in May to the glory of St. Philip Neri» (Una grande istituzione sociale: I monti frumentari, 1973, Acerra). This is a detail that indicates what the holidays were for our people: in the midst of misery, and precisely because they were poor and exposed to the radical fragility of life, life was celebrated on feast days, we celebrated together to continue to hope and to defeat death. And the Church, here truly a teacher of humanity, understood and approved the loans of grain for special meals and desserts, which interrupted hunger and famine and said to the poor: "you are not always and forever poor". Today we have forgotten what holidays are because we have forgotten the art of the little, the great art of the poor. And so, in the abundance of "grain", we die from festive famines.

Some statistics express the expansion of the Monti Frumentari were: in 1861 in Southern Italy there were 1,054 Grain Banks, double those in the North, of which about 300 in Sardinia alone; in central Italy, particularly in Umbria and the Marche, there were 402 Grain Banks (P. Avallone, "Il credito", in Il mezzogiorno prima dell 'unità, by N. Ostuni and P. Malanima, 2013, p. 268). Why did they become extinct? In 1717, in the diocese of Benevento, of the then Bishop Orsini, there were "157 Grain Banks", not branches but independent entities (P. Calderoni Martini, Fra Francesco Maria Orsini and the agrarian credit in the XVII, Naples, 1933). In the eighteenth century, among the protagonists of the debates on the Grain Banks were the best "civil" economists, from Giuseppe Palmieri to Francesco Longano, the student of Genovesi who from 1760 to 1769 supported and then replaced his sick master in the lessons of Civil Economics in Naples. The Monti were real economic, financial and ethical institutions, not ‘pious works’.

The Franciscans, and then bishops and citizens understood that when dealing with poverty and the scarcity of money, there is a simple solution which is often forgotten: to reduce the use of money. They understood that an economy could be created without money: if it was grain that was necessary and scarce, then it was grain itself that could become the currency, without the need for another intermediary. They skipped a step, shortened the economic supply chain and lengthened the life supply chain. One step less became one step more. They innovated by removing and reducing a degree of intermediation. Today there are billions of people excluded from money, who need new local and global, non-usurious financial institutions. Will we be able today to imitate the ethical and civil creativity of yesterday's Franciscans?