The land of We/3 - In Latin capitalism the links are in the day to day dynamics of businesses and banks

by Luigino Bruni

published in Avvenire on 07/10/2023

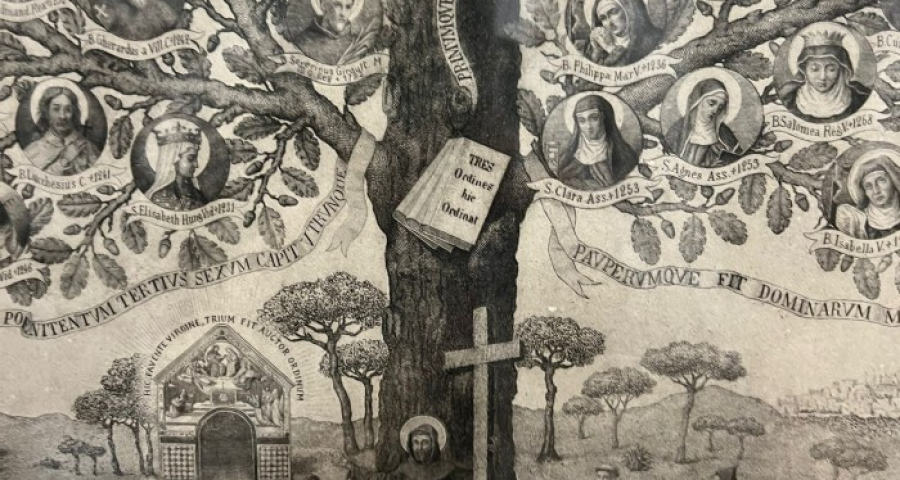

The economic institutions of our meridian lands began in a hybrid way and continued so, as long as the way of doing business in the lands under the shadow of the Alps retained the characteristic and unique traits, which today are disappearing into the general melee. Following Augustine and Luther, the Protestant North distinguished the ‘city of God’ from the ‘city of man’ and therefore, the market from the gift, the contract from gratuitousness, solidarity from the enterprise, and profit from non-profit. In the Age of the Counter-Reformation, Latin Humanism reinforced the promiscuity between these worlds and regions. And so it generated parish priests who managed cooperatives and rural banks, entrepreneurial families, friars who embraced extreme poverty while founding banks for the poor.

There are now many who think that the community, the Mediterranean and Catholic economy, that ‘land of We’ made up of close relationships and warm bonds, where street vendors sang songs in the streets (the Sicilian abanniata) and in the markets exchanged mostly words, has nothing good left to say; that Latin capitalism is gone forever where solidarity was not entrusted to 2% of profits because solidarity was implicit in the ordinary dynamics of businesses, banks and cooperatives; ours was the solidarity of the ‘during’, not that of the ‘later’. That Mediterranean world where wages were not left to the vicissitudes of the ‘labour market’ because that ‘salt’ was something more than and was different to a commodity. Life and suffering had taught that when work becomes a commodity, its salary-salt becomes too foolish to flavour good and wholesome meals. And so, what remains of communitarian economics is increasingly seen and treated like the old “Singer” (sewing machine) of our Aunt or the “Letter 35” (typewriter) of our Grandfather.

It is clear that the community is ambivalent because real life is ambivalent. And therefore the community is life and death, siblinghood and fratricide, friendship and conflicts, hugs and fights, tears of joy and pain, together. And a society that only sees relationships as deception, that adores the free individual because he is free from all human relationships other than those of the market, contracts and social networks (which are the same thing: the ‘like’ of Facebook is the ‘like’ of the sovereign consumer), can only flee from the community, from every community made of flesh and blood.

Yet there must be something wrong in all this discourse, in this discussion which is becoming the only one, something that the environmental crisis is clearly revealing to us every day.

In these weeks we are seeing that the Franciscans had a different idea of person, community and economy. They made the entirely charismatic choice, to go and live in the heart of the new medieval and Renaissance commercial cities. They left the valleys and took to the streets and became friends with the merchants and citizens, and often they understood them. And when they wrote about economics and money, they did not look at the world from the level of theological treatises, generally written by those who had never seen real merchants and bankers (the impression that the theologians who wrote about economics made on merchants is very similar to that of politicians today, who write laws for an economy they do not know Instead, they placed themselves at the low level of the market stalls, and there they met the eyes of the mercatores and another economy was born, different kinds of banks emerged, other kinds of Monti.

Those Franciscans were able to innovate because they got their hands dirty with economic matters, even running the risk of making mistakes, because the earth is changed only by those who walk on it and do not take refuge in the ethereal purity of the heavens; the new heavens cannot be found without the new lands. And they made mistakes, including the serious one, of the anti-Semitic tone of their battles against usury, based on the idea that it was only the Jews who lent money at usury. That idea was wrong, because a lot of usury, especially the main kind, was carried out by good Christians, rich banking families who lent to rich Christian merchants, cardinals and popes; the Jews were left almost only with small loans, sitting on their benches under the awning with the red carpet. Everyone saw them there, while the large usurious contracts of the powerful Strozzi, Medici or Chigi remained invisible to most people, including friars; big finance has always had its strength in invisibility. Many Catholic usurers had brilliant political careers (Massimo Giansante, The Honoured Usurer, 2008), in a European finance that, unlike the bad anti-Jewish legend, was also, and in some cases above all, in Christian hands (F. Trivellato, Ebrei e capitalismo: storia di una leggenda dimenticata, 2021).

We find it very difficult to understand the profound reasons for the ancient moral struggle against usury. The main one is a clear and strong principle: ‘you cannot profit from future time, because that is the time of children and descendants’. This is why our generation is a usurious generation, because it does not know "how to think about the common good and the future of children" (Laudate Deum, 60), those "children who will pay for the damages of our actions" (LD, 33). A usurer is anyone who speculates on their children’s time today. The poor of today are also and above all the children present and future, who must be protected from our individual and collective usury.

Let's go back to the wonderful history of the Franciscans, which today here in Assisi (where I am for the ‘Economy of Francis’) stands out with a dazzling light of the future. Francis is the name of tomorrow, not just of yesterday.

When the action of the minor friars in founding the Monti di Pietà (which gradually became banks in the cities), was attenuated with the Council of Trent, the Capuchin friars took up the baton and for over two centuries built hundreds of Grain Banks. The minors operated mainly in the cities of the Centre-North, because in those monetary economies it was essential to circumvent usury with the great intuition (of Jewish origin) of the pawnbrokers who became their Monti di Pietà. There, the families’ possessions (clothes, furniture, work tools, jewellery: almost everything, except weapons) were liquidated in money, which was essential in the city where the division of labour prevailed. In fact, there were few objects pledged to the Monte (pawned) that were redeemed upon repayment of the loan, because those Monti performed a mixed loan-purchase function. In the countryside and in the South, on the other hand, where the economy was mainly non-monetary, the Grain Banks were born, with the simple and extraordinary innovation of wheat used as currency. In the countryside and in those subsistence economies there were few assets which could be pledged, and so the guarantees, which are necessary in every form of finance, were personal ones, such as surety. Credit thus returned to its ancient etymology of believing, trusting and believing above all in someone, therefore in people. In the event of insolvency, the Monti di Pietà sold the pawned objects, and the Grain Banks became ‘insolvent‘: "In fact, since there were no objects to sell in the event of failure to repay the loan, the Monti became ‘insolvent’" (Paola Avellone, All’origine del credito agrario, p. 33). Communities are also made up of these fragilities.

It is a great, long and unknown love story, entirely evangelical and entirely civil, one of the brightest pages in our economic and social history. Let's then add a few more pages.

Eufranio Desideri (1556-1612), who would become San Giuseppe da Leonessa, was one of these tireless Capuchin friars who built dozens of Grain Banks in the villages of the Sibillini and the Monti della Laga, from Amatrice to Norcia, in almost all the villages and towns of those fragile lands. Thus we read in the testimonies of his companions: "When Brother Joseph preached in Bourbon, I was his companion and there was a great famine in that land. Two baskets full of bread were brought by two women. Brother Joseph arrived at the church, blessed the bread and ordered it to be distributed to the poor: there were about 200 of them. We began distributing the bread. In the meantime many more people had come, but in the end there was enough for everyone, indeed there was some left over which was kept in the houses: in ours there were 3 or 4 rows of 12 loaves each left" (http://www.manoscrittisangiuseppe.it/la-vita/). The multiplication of the loaves and fish are a constant in our Christian history, it has been repeated a thousand times in those places where ‘two women’ or ‘a boy’ gave something, and someone else still believed in the miracle of bread for the poor.

Fra Giuseppe was proclaimed a saint by Pope Benedict XIV in 1746, the Pope who took the name of Benedict XIII, that is, Francesco Orsini of Gravina, the ‘farmer pope’, who inspired hundreds of Grain Banks. The year before Benedict XIV had written the Vix Pervenit, the first papal encyclical that legalized interest on loans. In that Encyclical, loans in ‘wheat’ are also mentioned (VP, 3.V), demonstrating how relevant and important the experience of the Grain Banks still was. And, although it is a document that has gone down in history as the legitimization of interest-bearing lending, almost all the Encyclical is instead dedicated to reiterating the illicit nature of usury and interest-bearing loans, which are legitimate only in particular and precise conditions (variants of the ancient ‘emerging damage’ and ’loss of profit’) and "from these derives a completely just and legitimate reason to demand something more than the capital due for the loan" (VP, 3.III). For the rest, he reiterates that "any gain that exceeds capital is illegal and has a usurious nature” (VP, 3.II), which should make those who earn in this way feel "ashamed" - that was a world where the ethics of shame was still effective. A few years later, within the same civil and spiritual tradition, Antonio Genovesi wrote: "The rule: you have the right to give interest to your brothers; The exception: provided they are not poor." (Lessons in Civil Economy, 1767, II, chap. XIII, §20). The poor are not asked for interest: the return of capital is enough. We have forgotten all this in which ancient civil tradition was proficient.

Franciscanism has given us many things, some of them wonderful. Among these the dignity of the poor, who must be esteemed before being helped, because without the esteem of what the poor already are, no not yet good can come about: "I remember that on Sunday, when our convents usually receive a large amount of white bread, Brother Joseph asked me why I gave black bread to the poor who knocked at the door. And with great emphasis he said to me, ‘I want you to give the white bread to the poor.’” The value of white bread for the poor could only be understood by Francis, and his friends of yesterday and today.