If we want to bring the modern spirit closer to Jesus' message of life, we need to purify theological language, starting with the economic and commercial language.

by Luigino Bruni

published in Messaggero di Sant'Antonio on 12/07/2024

The first to use the economic metaphor in the New Testament was St Paul who, in his First Letter to the Corinthians, even uses the word price: «You were bought at a high price» (7:23). Since Paul is a giant of Christian theology, many theologians from then on thought that one could not talk about theology without using the metaphor of the ‘price of salvation’. Saint Paul, however, uses some other metaphors in his letters, too, including the sporting one (cf. 1 Cor 9:24-26). Yet no theologian of the past or present has ever thought that such a metaphor was necessary to explain Christian theology. Instead, a real and actual “economy of salvation” was derived from the economic metaphor, which would justify the existence of a kind of contract with prices to be paid and collected, and which would see Jesus as a “divine merchant”. Forgetting that biblical metaphors are always the daybreak of debate, points of departure. The other half of the argument has to remain unsaid: only partial metaphors leave a gap between the mystery of God and our theological ideas about Him.

I am convinced that the use of economic language by theology has hurt both theology and economics. It has not helped us understand what economics is, nor has it helped us understand the heart of the Christian mystery, which is all about gratuitousness - charis. The use of economic language to explain the Christian faith has, in fact, led to the theology of prosperity (and thus to the theological legitimisation of meritocracy that is generating the blaming of the poor). It has also created an exaltation of sacrifice, which has become very deeply rooted in the Catholic culture. As a reaction to Luther, who waged a pitched battle against the idea of the Mass as a sacrifice (‘The Mass is the opposite of a sacrifice’: Luther, Complete Works), sacrifice became, in fact, a pillar of Catholic theology, liturgy and piety. The cross of Christ became a praise and a sacralisation of our crosses: ‘Crosses come from God. Crosses are necessary because God has ordained so. True penitents are always crucified’. (D. Gaspero Olmi, Quaresimale per le monache - ‘Lenten /reflections/ for Nuns’, 1885). Thus, in the age of the Counter-Reformation the offering of our sufferings to God became the most flourishing economy in the Latin countries - while trade and businesses were developing in the North - fuelled by a proliferation of penances, especially in women's monasteries, where sufferings sought as a form of love for Christ became the currency of a new trade between earth and purgatory.

But if we do a serene reading of the Gospel, a question immediately arises: how were we able to believe that the loving God of Jesus was a “consumer of human pain”, that the first fruits he most liked were our sufferings? Not least because the Bible had taught us well that deities who love the blood of their children are called idols. The biblical God, the God of Jesus, is not an idol, because he does not want to increase the pain of his sons and daughters, but to reduce it: ‘I desire mercy, not sacrifice,’ Hosea and Jesus repeat to us. The biblical God does not love sacrifice, because he loves us and does everything to remove us from our crosses. Sacrifice is an ambivalent word even in human relationships - it is dangerous to read love as a willingness to sacrifice oneself for another - and it is even more dangerous when it is used to understand the relationship between us and God. If we want to bring the modern spirit closer to Jesus' message of life, we need to purify theological language, starting with the economic and commercial language.

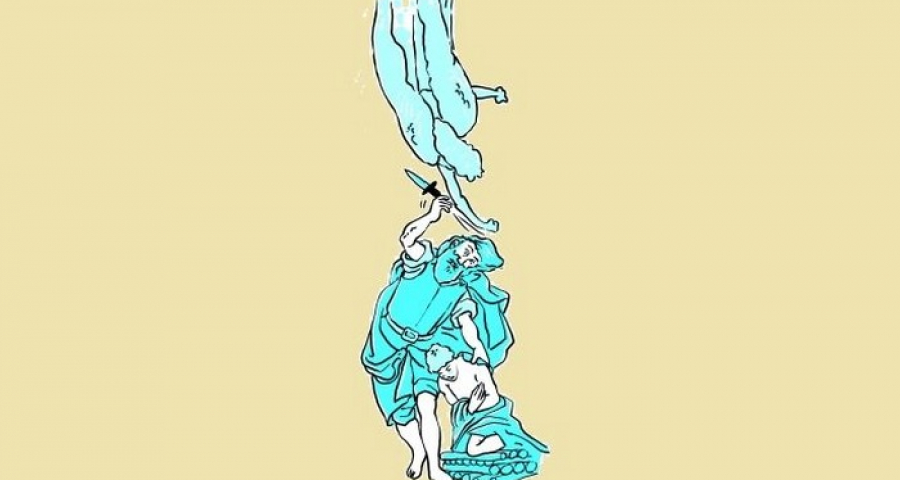

Photo credits: © Giuliano Dinon / MSA Archive