Consumer sovereignty was one of the great innovations introduced by US-based capitalism in the 20th century. Today, however, consumption is changing in nature, because the market has changed

by Luigino Bruni

published in Il Messaggero di Sant'Antonio on 01/10/2023

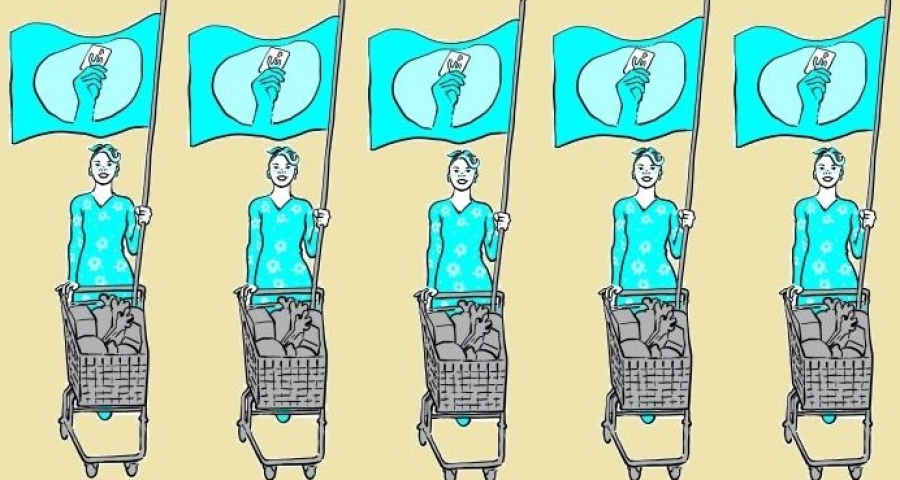

There is one aspect of our capitalist society that is not yet sufficiently discussed by economists and philosophers. I am referring to the absolutization of the consumer category. Consumer sovereignty was one of the great innovations introduced by US-based capitalism in the 20th century. At first, especially after the First World War, the arrival of this new protagonist in civic life was welcomed as a good novelty, and in part it was so. Consumption in the markets, consuming itself, was seen as a form of modern freedom, creating new opportunities and a new type of equality: even if I am a blue-collar worker, even if I am not highly qualified, even if I am not from a renowned family, even if I am not part of the elite, when I go into a shop with money I can buy the same car as the people of rank. At the moment of purchase I feel equal to those in leading roles and the rich, I feel second to none. This first season of mass consumption was an important step in democracy, first in the West and then all over the world (today these phenomena are especially important in Africa and Asia). Money doesn't even smell of social class: I may not be able to speak elegantly and eloquently, I am the descendant of peasants, but when I come to your shop you have to treat me with the same dignity with which you treat gentlemen.

Today, consumption is changing in nature, because the market is changing (or has already changed). Globalisation, first, and social media, later (with the for-profit multinationals that run them, let us not forget), have made the paradigm of consumption the new paradigm of democracy. In fact, market consumption has a few clear and simple rules:

1. the consumer is the only one who can decide on his or her preferences and tastes; 2. if I like a good or service, I buy it, if I don't like it, I don't buy it; 3. in the world of things, once we are in (with purchasing power or with debts) we are all equal, there are no hierarchies of any kind; 4. in the market you cannot impose anything on me without my consent. The 'like' on social media has been taken directly from the consumer world, where the only valid things are what the individual likes and dislikes. Therefore, no one can impose on me, whether from outside or from above, choices and goods that I do not like, that I have not freely decided to buy or not to buy. So much so that an axiom of liberal economic theory (the so-called Public Choice) says that the market does not act by majority (like politics) but by unanimity, since it is based on contract, the logic of which requires the consent of all participants in the exchange (Buchanan and Tallock).

How far can this reasoning go? If the consumer becomes the new global citizen, the question becomes: will these consumer-citizens be able to accept doing things they do not like? Will they be able to accept, for example, laws they do not like and suffer their consequences even when they do not like them? Will they accept the coercion of authority, or are we forming new citizens who will only want to pay the fines they want, who will only go to jail if they agree? Until today (or yesterday), laws and penalties were decided democratically, i.e. by the majority of citizens and with guarantees for the minorities, but the laws in force do not require the 'like' of every single citizen, let alone of those who have to abide by them. The serious question then becomes: will democracy survive the consumerist post-capitalism of the 21st century?

Photo credits:o: © Giuliano Dinon / MSA Archive