A social system that rewards the already capable does nothing but leave the less capable, who are generally not so because of demerit, but because of their living conditions, further and further behind.

by Luigino Bruni

published in Il Messaggero di Sant'Antonio on 04/06/2023

The resignation of Senator Carlo Cottarelli because, among other things, he did not see his party as strong enough in its support for meritocracy, has once again drawn attention to the meaning and ideology of merit in our time. Merit has always been an ambiguous word, because it is deeply linked to the fascination that merit exerts on all of us. We would all like to be deserving of our successes (less of our failures), no one likes to think that the nice career they have had is only the result of good luck and recommendations.

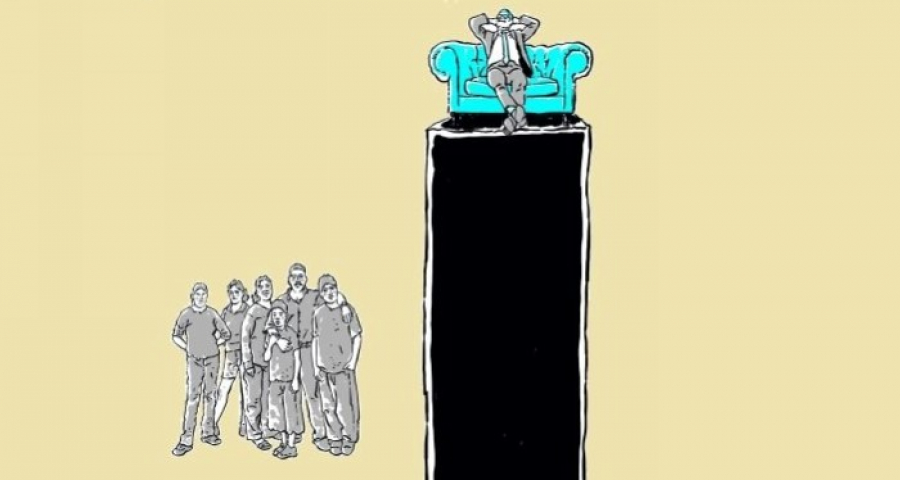

But if we take a look at how merit is used, yesterday and today, in the concrete choices of the economy and society, we realise that it has almost never been on the side of the poor, who have often been discarded and then blamed because they were considered undeserving, thus convincing them that they were not only poor but also at fault and cursed. The word merit derives from (Latin) merere, meaning to earn, from which mercede (earnings, payment) and meretrice (prostitute) also derive. Meritocracy is the ideology of merit that, like all ideologies, takes a word that we like and that fascinates us, and then manipulates and perverts it. And so, in the name of appropriating a value to the deserving and the poor, the meritocratic ideology has become the ethical legitimisation of inequality.

All it took was to change its name and inequality went from being an evil to being a good. There were three steps: 1. considering people's talents a merit and not a gift; 2. reducing people's many merits to those easiest to measure by consultancy firms (who today sees the ‘merits’ of compassion, meekness, humility?); 3. reading talent as merit leads to remunerating merits differently and thus widening the gaps between people.

The misunderstanding about merit can already be found within our wonderful Constitution, which states in Article 34: “The able and deserving, even if deprived of means, have the right to reach the highest grades of studies”. It is not by coincidence that the new government has relied on this article to justify changing the name of the Ministry “of Education” to that of “Education and Merit”, creeping into the loophole left open by the ambiguity of that Article 34.

Merit lovers say: “merit is not just talent, it is a combination of talent and commitment, so what is rewarded is personal commitment”. However, these meritocrats forget the crucial element: being able to commit oneself is not a merit either, it is above all a gift. Coming home from school and having time to do homework, instead of having to work, is not a merit. If we are honest, we have to recognise that what we are and become is 90 % gift and 10 % merit; meritocracy, on the other hand, overturns this percentage, and makes that slender 10 % the cornerstone of the edifice of justice.

Being institutions, schools must be anti-meritocratic: that is, they must reduce those asymmetries of starting points that have nothing to do with the merit of our children. A social system that rewards the already capable does nothing but leave the less capable, who are generally not so because of demerit, but because of their living conditions, further and further behind. Don Milani, whose centenary we are celebrating this year, knew these things very well. He knew that his boys in Barbiana were not undeserving; they were not at fault, they were just poor. May this centenary make us reflect on the ideology of merit that is becoming the new religion of our time, a religion without gratuitousness and without God.

Photo credits: © Giuliano Dinon / Archivio MSA