The soul and the harp/26 - There is also a good form of wasting of time and things, for the sake great and true relationships

By Luigino Bruni

Published in Avvenire 27/09/2020

"Maximum restoring and relief came to me from the comfort of my friends ... the talks, laughing together, the exchange of affectionate courtesies, the occasional disagreements, without rancour, like every man has with himself, and the more frequent agreements, untainted by the same very rare disagreements; being each other's sometimes teacher, sometimes disciple, the impatient nostalgia of those who find themselves far away, the festive welcome offered to those who return".

Augustine, Confessions, IV

Psalm 133 is known as the psalm of fraternity, which while it speaks to us of the beauty of the fraternity of blood tells us of a different kind of fraternity of the spirit.

Fraternity is a great word of the Bible because it is a great word of life. It is simply another name for happiness. Brothers and sisters are part of the ordinary landscape of home. They are an essential component of our life. The love for a brother or a sister does not have any connotation of Eros or of philia (we may not always be friends with our brothers or sisters, yet we love them very much). It is another kind of love, different and special, which uses the language of flesh and guts (and thus resembles our love for our parents). A typical note of fraternity is that visceral pain we feel when a sister or a brother falls ill, when he or she suffers, when he or she is offended or humiliated - seeing a sister suffer is one of the greatest pains we males can experience. There is, moreover, a typical and very special kind of joy involved, perhaps one of the greatest on earth. This is what parents, especially mothers, feel when they see that their children love each other. When they see them esteem each other, bless each other, console each other, defend each other, help each other, and celebrate together.

It is not surprising then, that in order to express Job's greatest blessing of happiness, the Bible should speak of his sons and daughters eating together: «His sons used to hold feasts in their homes on their birthdays, and they would invite their three sisters to eat and drink with them» (Job 1,4). The reference to the sisters is important here, because if it is already nice enough to find yourself celebrating among brothers, it is downright wonderful to find yourself between brothers and sisters, when girls and women with their typical grace enhance the charis and the feast in a home. This typical joy for the harmony of children increases with the years, because if it is nice to see your children and young people love each other, and it is even more beautiful to see them love each other as adults, when distances and reasons for disagreements and divisions naturally grow. Perhaps there is no more beautiful end-of-life for a parent than seeing daughters and sons who have truly cherished their mutual love; how great that love is, taking on all the different tones and shades of agape. The love of a child who would prefer to give up his or her own personal legitimate interests just to avoid this special suffering for his or her parents.

Hence, we can easily imagine that the beautiful Psalm 133 was composed, or at least sung, by a mother. On a feast day, perhaps on the evening of Pesach, a woman looked at her children sitting around the table, and in the depths of her heart this prayer was born, one of the most beautiful prayers there are: «Behold, how good and how pleasant it is for brethren to dwell together in unity!» (Psalm 133,1). The psalm of fraternity. The Hebrew word that the psalmist uses to describe this special beauty and sweetness is twb, the same word we find in the first chapter of Genesis when creation was completed: "God saw all that he had made, and it was very good (twb)" (Genesis 1,31). Perhaps to tell us that when brothers and sisters "sit together" the family returns to stroll in the Garden of Eden, a certain primal innocence and purity returns, death is overcome again, we eat the fruit of the tree of life and we live an eternal youth - as long as someone calls us "son" or "daughter" we will always be young. The two metaphors that the psalm uses to develop the theme of fraternity are very beautiful indeed and deeply rooted in biblical language and symbolism: «It is like precious oil poured on the head, running down on the beard, running down on Aaron’s beard, down on the collar of his robe. It is as if the dew of Hermon were falling on Mount Zion» (Psalm 133,2-3). The oil was a sign of the consecration of priests (Aaron), but also of kings, of prophets, and it was the gesture that welcomed the arrival of a guest, who was honoured by having his weary body anointed with scented oil. An overflowing of oil that drips from the head to cover the face, the beard and then continues down the robe.

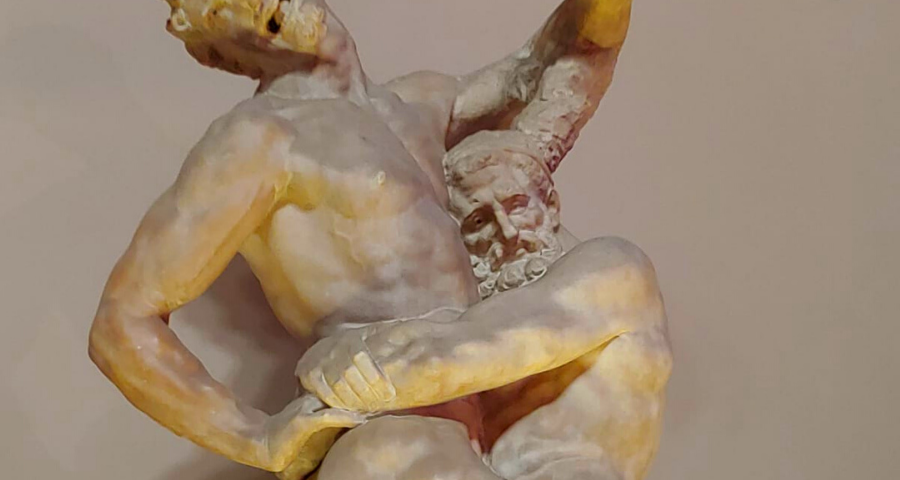

An image that speaks of the surplus or excess of fraternity. Fraternity is the opposite of avarice, if you do not hand your brother a cloak, he is handed a tunic either, because it is what we do not have to give and instead chose to give anyway that expresses what a brother or sister truly is. It is the oil that a woman poured on Jesus' feet, which was worth ten times more than the price of betrayal. An economist would never understand this waste, and would instead continue to blame the inefficient excess. There are no interest bearing loans among brothers, not even at the inflation rate needed to, at the very least, recover the expenses. One simply gives to a brother: lending is a good business verb but it is not a verb of fraternity - "here is the money you needed: you will give it back to me when and if you can". A brother has the same dignity of a king, a priest or a prophet, not an ounce less; and when he comes to visit us at home we must honour him as guests are honoured in the Bible. As Abraham and Sarah welcomed the three men at the Oak of Mamre, as Solomon welcomed the Queen of Sheba, as the good shepherd of Psalm 23, as the two sisters welcomed Jesus in Bethany. Like the widow who hosted Elijah in her house and gave the prophet the last handful of flour and the last drop of oil she had left. Prophets and brothers, and sisters are not given what is superfluous, they are given what is necessary, for them you would go amiss of your last bread. Our daily bread is a gift from the Father, but it almost always arrives at the hands of a brother, or a sister. When we leave our common home as grownups and a brother comes to visit our new home, you should honour him as the Bible honours its guests. And even if he comes to visit often, the day of his visit is the day of bringing out the most beautiful tablecloth, of setting new flowers. Time stops, touching eternity. The hours spent with your brothers and sisters last longer, fraternity extends our life. All guests are a blessing, but the blessings that brothers and sisters bring, honoured as angels, are infinite.

The second image is that of dew, another beloved word from the Bible. The dew of the highest mountain that mitigates the long droughts. It is always surprising to find grass wet with dew upon waking up during our torrid summers, a gift of a different kind of freshness when there is no water. Dew is a great image of gratuitousness, a gift that is there for us, for everyone. Like dew, fraternity needs a clear and calm windy night in order to light up the field of our lives. Like dew, fraternity is that given freshness that accompanies the aridity of life, arriving without giving a second glance at our virtues and merits. Fraternity is anti-meritocratic, both when it is looked at from the perspective of the parents, and when it is observed with the gaze of your other brothers and sister - even if the elder brother in the parable is there to remind us that meritocracy is a temptation and threat to fraternity, that if not overcome every day generates various forms of fratricide.

The oil dripping from Aaron's beard then reveals another fundamental element of fraternity, which is the other side of the surplus: a good kind of waste. As with other first words of life, there are two sides to the word waste, a good and a bad side. The good one belongs to fraternity, which also thrives on waste: the passing of time, words, food. The waste of time drives away haste, the enemy of all primary relationships. The waste of words is the blessing of endless evenings and nights spent saying with a hundred words what we could say with only ten, because those wasted ninety words in excess are the words that we give to each other when freed from the slavery of efficiency. Moreover, there is no family celebration where food does not exceed what is necessary, where what seems a waste is only the celebration of a greater good, an archaic and deeply profound language to say that those hours spent together are worth more than the national GDP, that this relational good is the greatest form of good. In fraternal meals, if you do not eat too much, you just have not eaten enough. And even when poverty offers us only five loaves of bread and a couple of fish, eventually we will still have to take home seven stores of leftovers.

Yet, despite all this beauty, the Bible presents us with natural brotherhood as something ambivalent, and generally problematic. Abel, the first brother is a murdered brother. Jacob and Esau fight, battle and separate, then Leah and Rachel, the two rival sisters, then the story of Joseph sold by his brothers, Jephthah chased away by his half-brothers, Amnon's violence on Tamar, up until the brother of the prodigal son. In the Bible, the cases of brothers and sisters who love each other like those of Psalm 133 are few and far between. Perhaps to tell us that the brotherhood of blood, however great and often wonderful it can be, is not enough to understand biblical humanism, the new people, the Covenant, and the new and different universal biblical and then Christian brotherhood. Therefore, in order to show us its new brotherhood not connected by blood, the Bible is not content with praising natural brotherhood, and instead highlights its insufficiency. We too know that that first natural fraternity will never be full and true humanism if it does not eventually flourish into a second kind of fraternity. One does not remain brothers and sisters for life if at a certain point that bond of blood, already great and beautiful, does not become even greater and more beautiful, blooming into agape.

Brothers and sisters remain brothers and sisters until the end, if one day they also become friends, and mother and father of each other. Fraternity is dawn; it is dew, but that sun will not be able to keep all the light of dawn shining all thru noon, if the blood does not also become spirit, and if we are not reborn in this spirit. The Bible, however, also wanted to give us Psalm 133 with its splendid words because, while it reminds us that fraternity is fulfilled by dying in the flesh and rising in the spirit, those brothers and sisters sitting together are among the most beautiful things under the sun: «For there the Lord bestows his blessing, even life forevermore» (Psalm 133,3).

Download pdf article in pdf (277 KB)