The soul and the harp / 6 - Prayer brings the Creator out of the cage-metaphors created for him

By Luigino Bruni

Published in Avvenire 03/05/2020

"In my notes you will find neither a Jewish comment nor a Christian comment.

Man pains me: I have no other guide. And as an act of pity this is what I transmit."

Guido Ceronetti, The book of psalms

Psalm 6 helps us to remember that suffering and illness are not wanted by the Father who, if we ask him to, knows how to "move" closer.

Anyone who has crossed the chasm of a serious illness learns that that illness is not just about the body. Or rather: he or she understands that the body is an interweaving of matter and spirit, it is spiritual flesh and incarnate spirit. Diseases are therefore questions, addressed to us and to others. They are among the few moments of truth that we experience in life. When we find ourselves in a hospital bed that until then we thought was only meant for others, the time of fiction ends and that of truth and bare raw questions begins. We are no longer satisfied with the half-lies told to others and to ourselves: reports and diagnoses become languages of a new authentic relationship with life and with the world. This is why a disease can also be the announcement of a great blessing. The religious pitfalls of any illness lie precisely in that space between suffering and blessing. Ancient man addressed his questions first and foremost to God. We, however, have depleted the language and vocabulary of life and hence tend to address our questions above all to science and doctors. Nevertheless, if the disease becomes severe, sooner or later even the profound questions arrive: "Why me?", "What went wrong in my life?"; "And why?" Every now and then, even in the midst of our world, depopulated of gods, the terrible question may come back: "What have I done wrong to deserve all this pain?" It is very difficult to come out completely innocent from a serious illness.

Our questions rarely manage to reach God: we have trivialized him too much to feel him near us in the midst of the truth of our suffering. Our questions often come very close to him, they stop just a breath away from heaven, even if we do not know it - but the angels know and always see us. The first psalms of the Psalter present us with various models of prayer, that is, the different existential conditions from which man can learn and relearn to speak with God: encircling the enemies, unjust accusations, hope. Learn: the development of the psalms is about learning the art of praying. In the monasteries, liturgy was understood as an art form, as a profession - the ambiguous semantics of this beautiful word further reveals this to us. Psalms are many things; they are also an apprenticeship in prayer. On that day when the need for prayer is born within our soul, we can open the book of psalms, scroll through them one by one and stop at the one that we feel is our psalm; and as we start singing it, we realize that those are our words; we just did not know it yet: «When Jacob awoke from his sleep, he thought, “Surely the Lord is in this place, and I was not aware of it» (Genesis 28,16). And that first psalm, the one that the prayer taught us, will be our psalm - and in the end we will discover that the first and the last are really the same song.

With Psalm 6 the anthropological space of prayer widens again. A man is facing a long and serious illness. And asks: «Lord, do not rebuke me in your anger or discipline me in your wrath. How long, Lord, how long?» (Psalm 6,2-4). God is the first interlocutor of the two questions. Ancient man, then, added the horizontal dimension to the vertical dimension of these bare questions. God, the others and me: this was his ternary space. And so, after dialoguing with God, the psalmist (and us with him) looks for other allies in guilt, and the interpersonal question almost always arrives as well: "Who is responsible for what happened to me?"; "Who are my enemies?" Day after day the dialogue with one's soul and with God increasingly also becomes a dialogue with others, seeking the executioners around us: «Away from me, all you who do evil» (Psalm 6,8). My colleagues, my boss, the competition, my community, the doctors: we search the soul looking for a grammar of our pain. We are unable to resist for a long time without calling our suffering by name, because we know that only by calling out to our pain, it might be able to show us another unknown, and perhaps good, side or face.

Ancient wisdom had developed a complex hermeneutics, an ability to decipher pain, disease, and misfortune. This is also where a decisive dimension was added: illness and suffering were experienced as punishment for those who experienced it, due to faults of their own or of their family. That pain hence became the bill asked by heaven to restore a balance broken by a committed sin. This remunerative-economic vision of faith has always been very successful, because it is extremely simple. Very simple, and therefore too simple to be true. Such a faith works because it perfectly performs the function of saving the ethical balance of the world and justifying divinity, which thanks to this religious expedient always falls on its feet, and always comes out innocent from our misfortunes. This is how religions have often become moral mechanisms that save the justice of God by sacrificing the innocence of men.

Furthermore, retribution was to take place on this earth. The accounting between men and God did not extend beyond life: «Among the dead no one proclaims your name. Who praises you from the grave?» (Psalm 6,6). Death is the kingdom of nothing; and even if God lives in the heavens, earth is his home. His voice resounds in the sun, he needs the sounding board of the mountains, the seas, the infinite space of the human heart. A theology of retribution without paradise is even more demanding, and so it also uses our pain as currency to bring the accounts back to balance. In Psalm 6, however, the author does not accept his destiny, impassively or resigned. He talks, discusses, and argues with God and with his own misfortune. He asks God to change, to answer his question: "how long". He asks him to come back: «Turn, Lord» (Psalm 6,4). Re-turning alludes to the possibility that God changes direction, and is converted. The biblical God is a God who knows how to turn, if we ask him.

It is within these sentences that we find the theological and anthropological greatness of the Psalms. They are prayers to the God of the yet to be: they ask him to become something that he is yet to become. The man of the psalms does not feel imprisoned by his destiny or his faith and dares to ask God: "How long?". And so prayer meets with religion and resurrects it. This is also what prayer is about: a person who in the experience of his spirit no longer feels a slave because he has been freed and as a free man manages to free God from the cages in which theology and religion keep him locked up. That is why God needs our prayer, at least as much as we need God. Biblical prayer then becomes our first exercise of freedom, a liberated man who manages to free his God.

Then there is a last message. The words that the psalmist uses in the second verse (hwkyh + ysr) are the binomial of pedagogy; they are the expressions of the education of children by their parents and teachers. The translation that the biblical scholar Alonso Schokel makes of it is particularly beautiful: "Scold me without fury, correct me without anger". Until now, we had chosen the image of the judge and a rather forensic language for God (and we find them here in this Psalm 6, as well). Now prayer asks God to leave court and enter primary educational relationships. Hence, illness is no longer understood as punishment for atoning guilt, but as punishment within the educational paradigm of that world. And here the Book of Job returns, punctually, when a fourth "friend", Elihu, bursts onto the stage bringing with it the pedagogical explanation of suffering: «Or someone may be chastened on a bed of pain with constant distress in their bones» (Job 33,19). Job did not reply to Elihu, he was not convinced by the explanation of suffering as an instrument that God would use to give us a "lesson". Job was silent; the psalmist seems to accept the pedagogical explanation, but continues the dialogue and asks God to "return". He starts from the metaphor, but is not satisfied.

If we wish to repeat the experience of the psalmist today, we must continue asking God to return, and therefore free him from this pedagogical metaphor that so often appears in the Bible. After overcoming the legal and economic metaphors that have tried (and still seek) to trap the freedom of God within our concepts of remuneration, we cannot now feel calm and reassured by a religion that associates our sufferings with some sort of educational intention of God. We must at least live up to Job and stay silent with him, or live up to the psalmist and ask God to "return". And this is where something new about praying is suddenly revealed. When we now open the Bible and find a word, a psalm, a song of a prophet, the Bible continues to be alive and active if we are able relive the same experience of that ancient author; hence, if we dare ask God to become what he is yet to become, to keep changing, and to return for us, for me.

Therefore, we keep delivering God. We are the deliverers of God, and we did not know it. What infinite dignity!

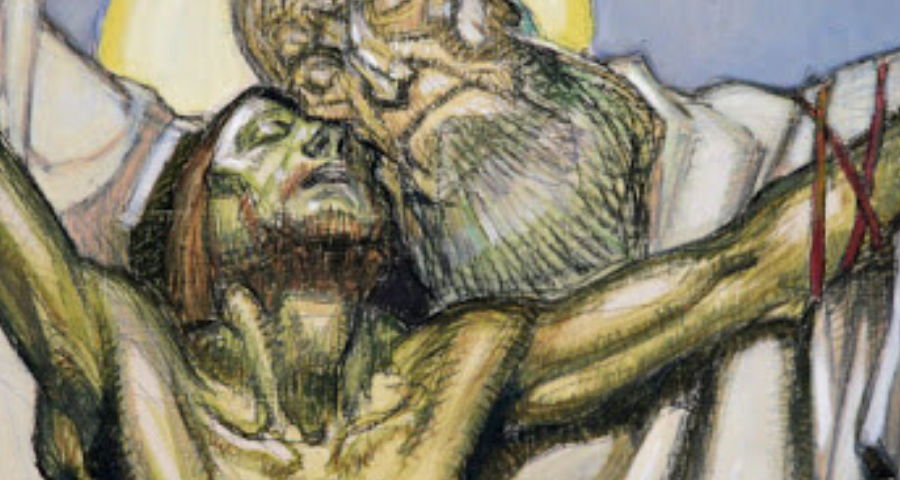

Illness and suffering are human facts; they are part of our repertoire. It is up to us to do everything to keep God out of the responsibility of our pain, and then not stop while reducing the pain and the suffering of human beings and all living beings. If we wish to see the hand of God during our sweaty nights spent in a hospital bed, we must be able to recognize it in those of nurses and doctors, in that of those who wipe our foreheads and cry with us. God does not wish for our pain, but accompanies us when it arrives. On Golgotha, the Father found himself on the same cross as his son, wiping his forehead, shouting with him. All the other spirits surrounding our pain are demons, and we must repeat with the psalmist: «They will turn back and suddenly be put to shame» (Psalm 6,10).

Download pdf article in pdf (407 KB)