Oikonomia/8 - Small well-deserved salvations attract us more than a great and undeserved one

Published in Avvenire 01/03/2020

"Often the vile work of a servant is more pleasing to God than all the fasts and works of priests and friars"

MartinLuther, The Babylonian captivity of the Church

The management of what is ideal and the trade in penances (what we know as incentives today) are an important part of the spirit of capitalism and big business. Even so, we moved away from the ecclesial "societas perfecta" to a "business community" instead.

Any utopia of a perfect society produces the image of a city of imperfect men and women, living their imperfection with a sense of guilt, which then becomes the main instrument to control and manage the consciences and existences of both individuals and the community as a whole. There is a relationship between the ideal of perfection and the spirit of capitalism. Monasticism, and later Protestant Reformation, both played decisive roles in this as well. The idea that Christian life was a path to perfection began to develop very early, until it became a pillar of medieval humanism, although neither the Bible nor the life and teachings of Jesus were ever centred on the idea of perfection. Biblical tradition, in fact, never placed people who were presented as models of moral perfection or of faith at its centre. Think of Jacob-Israel, his deceptions and lies, David, the most beloved king, who perhaps carries out the most cowardly murder in the Bible, or Solomon, the wisest king, who became corrupt. Salvation history is a history of moral imperfections that YHWH manages to tenaciously direct towards a mysterious salvation.

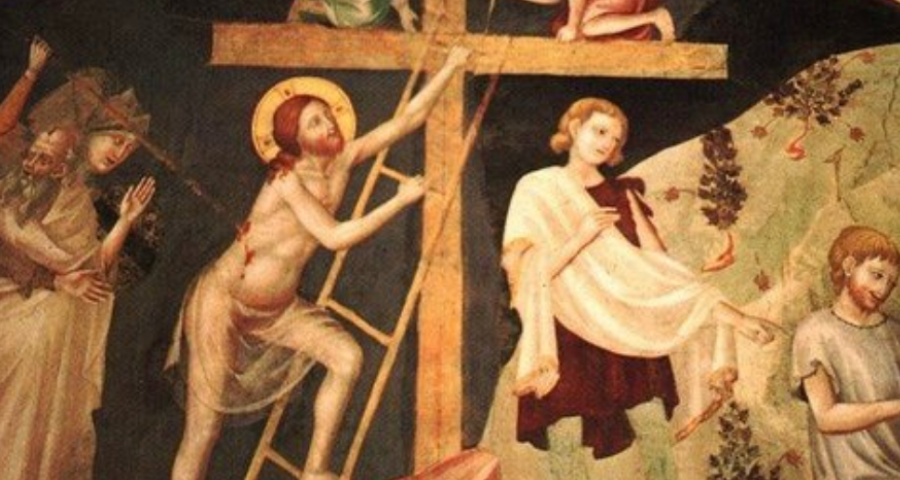

It is wrong to consider the Gospels as some sort of treatises on morality, let alone ethics of virtues. The beatitudes are not virtues. The message that emerges from the Gospels and from Paul is not that works or fasting will save us, nor does meticulously following the Law make anyone more righteous. Very little is said about perfection in the Gospels, because the message of Jesus is not a proposal for ethical perfection but a journey for women and men to become free from a vain ideal of perfection that only helps to produce neuroses and unhappiness. No moral path puts a scaffold or an empty tomb at its peak - not even those medieval traditions that represent Jesus as voluntarily walking up to the cross. The ethics of merit, the other side of the medal of all ethics of perfection, is in fact as far away as you can get from the original announcement of the Gospel. We are not loved because we are perfect, and nothing can attract the heart of the biblical and Christian God more than a sincere imperfection.

Nonetheless, Greco-Roman ethics of perfection eventually prevailed; and just as in the case with economic ethics, even in terms of perfection, medieval Christian ethics continued the moral ideal that prevailed in the Roman Empire. Partly because human beings find it much more attractive to build up a little well-deserved salvation than to welcome a great one, but as an undeserved gift. The ideal of perfection developed greatly in monasticism. After the age of martyrs, holiness was increasingly seen as moral perfection, and therefore as a means to fight against vices and cultivate virtues. And, as often happens, this humanism of excellence, interpreted as perfection, eventually became the ethics of imperfection and management of faults. Indeed, since imperfection is the empirical fact of life, indicating perfection as an ideal also implicated producing infinite and ineradicable feelings of guilt, the true masters of all ethics of perfection. Any ideal of perfection serves only to generate an endless series of errors and sins, and the numbers increase for every day that goes by. The fruit of any law lived as an ethical ideal is sin. The greatest value in any ethics of perfection does not lie in the ideal itself but in the gap between what is ideal and what is real, an infinite value because the concept of what is ideal is infinite.

Confession and penance then became the tools to manage eternally imperfect people who experienced the gap between their real life and the ideal as an eternal source of guilt. The "Christian" ethics of moral perfection spread throughout Europe starting from the monasteries. With asceticism seen as a universal image of perfection, people increasingly turned to private confession and the consequent penances, first behind their walls and then outside the monasteries. With monasticism, particularly Irish monasticism, confession began to become a private matter between a monk and the priest he was confessing to. With the privatization and individualization of confession (which in the early centuries was a public and community affair) came the privatization of penances as well. These became increasingly detailed and specific, until a very specific punishment with a relative "tariff" corresponded to every single fault or sin - hence the highly indicative name of tariff penances. As we can read in the pages of the “Penitential of Colombanus": «If someone has sinned in thought, that is, he wanted to kill, fornicate, steal, secretly eat, get drunk, beat someone, he shall do penance on bread and water for six months ... If someone has perjured, he shall do penance for seven years».

The passing of time brought a series of innovation and changes, introducing other forms of penance, such as pilgrimages, as well as a more objective aspect of the act of penance, in other words independent of the sinner. Partly because penances, which were additive and often came to dimensions, (in terms of quality and quantity), that were quite impossible to sustain for a single person. Hence the decisive innovation: penance could be performed by any person, not only by the sinner, because ultimately what really mattered was "satisfying" God. Without really asking for His permission, the Christian God thus became an infinite sort of creditor towards men and women eternally indebted to Him for non-extinguishable and continually renegotiated sums of money. The first global and universal stock exchange of the Middle Ages was in fact religion.

The idea that penance could be both exchanged, trafficked and marketed, a phenomenon that was also greatly favoured by the introduction of the monetary medium, began to take hold. Given this objective aspect, penance easily turned into a commodity, saleable and purchasable. Thus, penance was no longer linked to a single person, and the first derivative title in history was born, because penance could now be re-negotiated as an autonomous entity in itself - Gaius sinned and Tiberius made the pilgrimage. The penance market was further facilitated by the extension of penance originally only paid by monks to now also including lay people, gradually invading and taking over all of medieval Christianity. From the 12th century onwards, the combination of perfection-penances created the phenomenon of "switching lists" which allowed a short period of hard fasting, calculated according to precise algorithms, to become a lighter but longer one. The further invention of plenary indulgence associated with pilgrimages and the jubilee (the one launched by Boniface VIII in 1300 was fundamental), the extension of the objectivity and transitivity of penance even to the dead in purgatory, lead to the creation of increasingly perfect and abstract markets. The inequality between the rich and the poor therefore also increased, as those who had more money could easily be exempted from heavy penances.

Hence, we have now arrived at the threshold of Luther and the Reformation, when the economy of salvation and the economy of money were already deeply intertwined. From this point of view, it is true that a first "spirit of capitalism" had already developed in the medieval world, but it did not so much develop among the cloth merchants and banks in the Italian cities of the fourteenth century, as many centuries earlier among the penitent monks and in the markets of penances and merits. We have been able to give life in Europe in modern times to the greatest mercantile experiment in human history, in part because Christians for centuries already had become accustomed to reasoning and negotiating about prices, debts, credits in the most intimate spheres of life, of death, of God. The "subject leap" from religion to economics was quick and easy. A further question arises here as well, the same that we asked ourselves in the case of wealth seen by the Calvinists as a sign of being chosen: where in all this is the Gospel? It is difficult to discern. Instead, we have to say that the penitentiary tariffs were yet another unintended effect, this time entirely Catholic, operated by Christianity in the economic sphere, an effect that had little or nothing to do with the Gospel.

However, there is more, in addition to the abolition of religious orders, so that asceticism and vocation were no longer the privileges of an elite of religious people but became the ordinary life of all, especially in the workplace, Luther and his reformers also abolished confession and the management of penances. Direct expressions of the idea (in their eyes Pelagian) of salvation depending on one’s acts and works. Up to this point, the story is well known. Another side effect is known to a much lesser degree. Work became the new good place of that "bad" asceticism and perfection that had been expelled from the monasteries, and hence the economy became the area where the ideal of ethical perfection developed most in Protestant humanism. If, in fact, the ascetic vision of life as a vocation does not serve to obtain merits from God, asceticism, the ideal of perfection and vocation still have a meaning of their own in the economy. Hence, the meritocracy in Protestant capitalism was born centuries later from the Protestant criticism of the merits in religion, and from its criticism of the ideal of perfection in monasteries, centuries later, modern economy was born as its own kingdom of perfection.

Anglo-Saxon Political Economy and the great capitalist enterprise both form part of the same cult of perfection. Economic science is entirely built on the idea of perfection - perfect competition, perfect rationality, perfect information, and interprets any deviation from perfection as a failure of the markets and perfect rationality. In addition, while economic theory today is slowly reconciling with the concept of limits, the great business enterprises are the ones that continue cultivating the utopia of rational and efficient organization. The name of the moral perfection of capitalism is efficiency, and so the societas perfecta of the Church transitioned becoming part of the business community. The theological battle against salvation understood as moral perfection eventually turned capitalism into a profane place of a good kind of perfection, where job descriptions and incentive schemes occupy the same place tariff penances and penitential books used to have. "Perfectionism" (Antonio Rosmini) is in fact also one of the great pathologies of big business, which interprets any gap between what is ideal and reality as failure, producing the same great feelings of guilt in workers today as it used to do in medieval penitents.

The mechanism behind it is in fact the same: limits experienced as a source of guilt that must be expiated with accurately calculated penances. The incentives are these new penances, codified and objectified in new manuals for confessors. And even if the incentives do not explicitly present themselves as penances but as prizes or awards, in reality they are an expression of the same anthropology that considers human limits as "sins" and sees the gap between what is ideal and reality as failure and a source of guilt for "losers" unable to achieve the high standards set. Just as the medieval monk who, if left to live his natural life, was destined to a life of failure and penance enabled him to hope to be able to reduce the gap, so incentives make the natural and imperfect actions of workers move towards the ideal objectives set by management. The Gospel is good news because it constitutes a liberation from our abstract ideals, in order to be able to meet others and God in the perfect beauty of an imperfect life. It took us ages to understand it. We have almost forgotten this today, and so companies try to make a business of our desire for paradise, almost always sought in the wrong places.

Download pdf article in pdf (419 KB)