We need to be aware, and keep our conscience alert, that every time we allow a ‘no’ to enter our lives, that ‘no’ multiplies, becomes a mountain, and reduces the horizon of freedom for us and for everyone.

by Luigino Bruni

published in Il Messaggero di Sant'Antonio on 23/09/2021

In the 1960s, Thomas Schelling, the Nobel Prize winner for Economics, developed models that help us understand certain socio-political phenomena. In particular, he showed how self-imposed personal limitations that seem 'normal' produce, once aggregated and on a large scale, very radical outcomes that individuals neither wanted nor foresaw at the beginning of the process. If, for example, on the first day of school every little girl thinks: ‘I would not like to sit at a desk between two boys’, this individual preference will produce a class with all the girls on one side and all the boys on the other. And we could go on with other similar examples.

Schelling's scholarly work also offers important suggestions for democracy and community life. It makes us understand why certain 'macro' and collective phenomena that appear very polarised and extreme are the result of much less polarised and extreme individual preferences. In other words, ideological oppositions on ethical or political issues – on life, on sexual orientation, on immigrants, on Europe, on vaccines... – tend to become much more exasperated and polarised than people think when taken one by one, and this happens when we move from individuals to large collective subjects (parties, movements). Hence the experience that in private dialogues there is less opposition than in the parties or movements that those individuals vote for and are represented by. So a practical tip: if citizens do not want radical parties, it is a good idea to reduce the limitations and conditions of their personal preferences to a minimum, because a limitation that appears undemanding to us gets significantly amplified at a collective level.

ut let us also think about community life. In communities, those collective habits and practices which, seen from the outside (and sometimes even from the inside) appear bizarre or excessive usually arise from people who, taken one by one, are much less 'bizarre' than their community. Some habits (the way of praying, gesticulating, sitting at the table, speaking...) are not wanted by anyone taken individually, but are created thanks to the amplifications of aggregation. Managers must be well aware of these things, because conscience is the only way to prevent fundamentalist drifts; such drifts can be stopped if one is able not to approve of individual deformations which, taken in themselves, do not seem so serious, but become so when they are added to those of others.

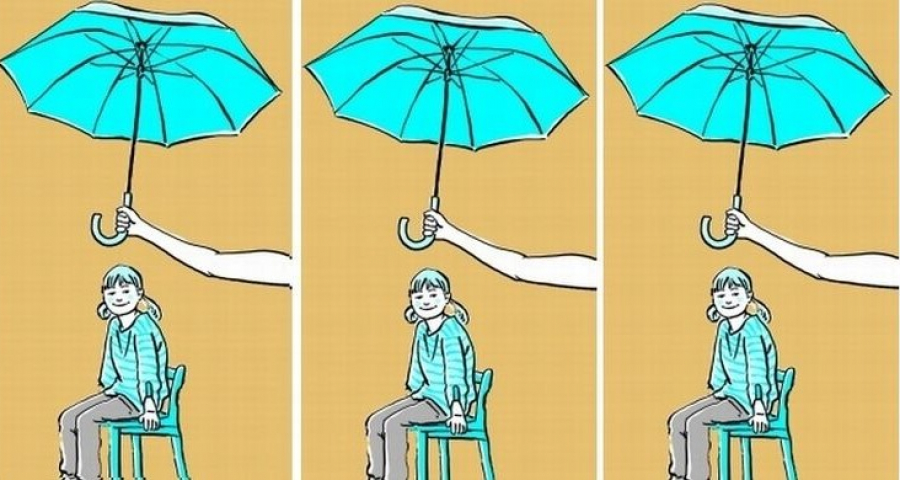

We need to be aware, and keep our conscience alert, that every time we allow a ‘no’ – and it can be a ‘no’ to a person, to a dimension of diversity... – to enter our lives, that ‘no’ multiplies, becomes a mountain, and reduces the horizon of our freedom and that of everyone else. And we may easily find ourselves in a world that we do not like either, just because, when we were still in time, we did not keep our hearts and our world wide open. In this respect, the education of children and young people is essential, because it is in the first years of life that these ‘no's’ begin to creep into the small openings of our education. They enter, grow and then multiply in our communities. We achieved the political and economic miracles of the second half of the twentieth century because the great pain of the wars had eliminated many ‘no's’ in our parents' education. Today, while we are in the midst of other wars, we must prevent those ‘no's’ from re-entering our hearts and producing new collective monsters. The challenge is decisive, we cannot lose it.

Photo credits: © Giuliano Dinon / Archivio MSA