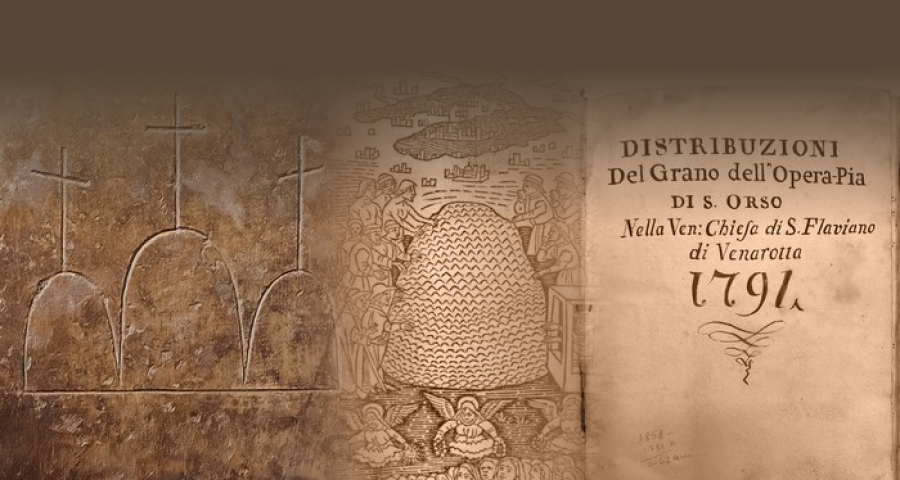

History - The collective project to get to know the micro-credit realities born in the 15th century at the instigation of the Franciscans takes shape

by Luigino Bruni

published in Avvenire on 11/02/2025

Our 'research from below' on the Monti Frumentari has started, in Italy and (unexpectedly) also in Spain and Latin America. Thanks to the many readers who set out to search the archives of their parish or diocese. A page dedicated to this search is now available ( https://www.pololionellobonfanti.it/notizie/riscopriamo-insieme-i-monti-frumentari/ ). We are initiating a true popular search, which if continued and expanded will allow us to reacquaint ourselves with pieces of local and national history and soul.

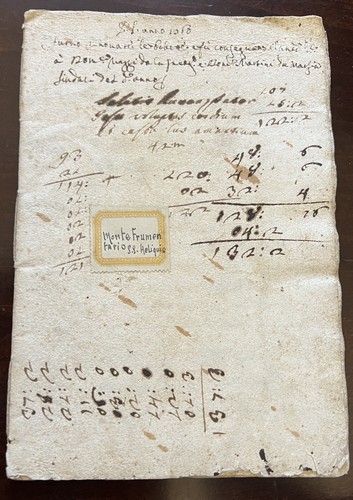

In the meantime, I went back to the archives of my parish in Marsia (AP), and, again with the help of my friends and parish priest Fr. Rodolfo De Santis, we tracked down other Mounts (we arrived at 14 within a radius of ten kilometers), and a third well-preserved book of the Monte Frumentario of Marsia (1797-1864), with the very valuable reports on the progress of the Mounts made by four bishops of Ascoli. It is impressive to note the attention the church paid to these institutions, out of a spiritual instinct that commanded it to make the gospel bread for the poor, lest it betray the gospel and the people.

In 1797, the bishop of Ascoli, Cardinal Archetti, made a pastoral visit to the parish of Marsia-a few months before he was arrested by French troops-and explicitly addressed his Monte frumentario. From his visit he saw that the "monte frumentario of Marsia for many years now has not been remitted, so that I order that it be as soon as possible reinstated in its entirety." Bishops and parish priests were really doing everything to keep these poor institutions alive, not least because the Mounts' capital was exposed to very poor years.

In the papers we often find the protests and complaints of the poor. We read, in fact, in the minutes of Bishop Gregorio Zelli's 1843 visitation: "Costing us that this year's harvest has been most distressing, we have therefore authorized by a supplication advanced to us by the Parishioners of Casacagnano..., to grant deferment to those who are really powerless." And in June 19, 1853, Pastor Paoletti wrote, "In the current year 1853 the grain loaned has not been remitted ... in view of the complaint made by the poor," same wording on June 18, 1855 and June 22 of the year 1857. For at least three years out of five the grain had not been returned, thanks to the complaint of the poor. The poor claimed and the bishop suspended the obligation to return the grain. Those proto-banks were able to hear these weak signals, to welcome them, to respond. They lived the nature of credit, because creditors before the cards believed the lament of the poor. How far away are too many of today's banks who believe the cries of the markets but when it is the poor who cry out too many times they turn away.

Our grandparents had their first credit experience thanks to grain credit: they associated loans with bread, with life. And so they were able to understand something also of the mystery of the Eucharist because it was a sacramental expression of that grain that became other bread of life thanks to the church. The bread of the Mass and the bread of the Mount were the same good grain. Thus was born the banking culture of our people. Today we no longer understand the mystery of the Eucharist partly because, in a virtual environment that has lost contact with the smell of the grain and its oikonomy of communion, we have forgotten the true value of any shared bread.

We should not think, however, that those Mounts were simply institutions of charity and almsgiving. They were certainly  charitable works, but in the sense of the Latin etymology of caritas, that is, 'that which is expensive,' that which has economic value. A commercial word that the Christians of Rome borrowed from the merchants, although they added a humble 'h' to it - charitas - to say that that word was also a translation of the Greek 'charis,' that is, of grace, of gratuitousness. We understand nothing of our economic model, the one that was there until yesterday and is disappearing today through ignorance and neglect, if we separate gift from contract, market from gratuitousness. It is this mixture, this crossbreeding of spirits that has created the spirit of meridian capitalism, which bears fruit and vivifies as long as it remains spurious and mixed.

charitable works, but in the sense of the Latin etymology of caritas, that is, 'that which is expensive,' that which has economic value. A commercial word that the Christians of Rome borrowed from the merchants, although they added a humble 'h' to it - charitas - to say that that word was also a translation of the Greek 'charis,' that is, of grace, of gratuitousness. We understand nothing of our economic model, the one that was there until yesterday and is disappearing today through ignorance and neglect, if we separate gift from contract, market from gratuitousness. It is this mixture, this crossbreeding of spirits that has created the spirit of meridian capitalism, which bears fruit and vivifies as long as it remains spurious and mixed.

The economic nature of these Mounts emerges when we read other pages of these ancient reports, "Debtors who have not returned the grain they have already received are excluded from participating in the new distribution" (Capodipiano, 1785). This credit rule-we have seen it-could be obviated, but returning the loan with 'growth' (interest) and excluding defaulters without just cause still remained the rule. The interest in grain (difference between 'ridge' and 'shaved') in some of the charters is quantified as 5 pounds of grain per quart, which corresponded to a little more than 6 percent - one quart, in nineteenth-century Piceno, corresponded to about 35 liters, thus 25.5 kilograms of grain; 330 grams formed one pound, so the interest amounted to about 6.3 percent (see, among other things, the minutes of 4.9.1856).

Trust was the first and great word of the Mounts. Bishop Zelli's 1835 decree on the Mount reads, "No one shall receive a loan without an obligation to be guaranteed by a suitable and solidary surety." In fact, in the accounting records it reads thus for each lend: "Serafino Serafini - sicurtà solidale Francesco Panichi," and on the line below: "Giuseppe Panichi - sicurtà solidale Serafino Serafini." Sicurtà, that is, personal fiduciary insurance, a surety that, however, the parishioners lent to each other: they were all at once guarantors and debtors. An ancient practice that to us, accustomed to today's surety bonds with little fide, seems bizarre-what value is the guarantee of one who vouches for someone by whom he is in turn vouched for? -, reveals to us instead something truly important.

The trust on which we built Italy was not the trust of the self, nor the trustworthiness of the isolated individual. The Latin and Catholic trust was the trust of the we: one trusted a community, one believed in those names of concrete people, because they were already bound together by a rope on which the trust of the grain also rested - Antonio Genovesi recalled that in Latin 'fides' means faith, trust and also rope. One trusted the 'known'. In fact, we read, "The right to participate in the benefit of distribution is restricted to the families of the parish only, and similarly of the parish must be the 'sicurtà,' not being able to oblige mayors to receive foreign sicurtà ...." (Capodipiano, 1785). Debtors and guarantors had to be from the same parish, and the parish base and this collective trust were the secret of the Mounts, which also led to their territorial multiplication. Of course, this supportive trust had its vulnerability, because, as in any rope, when someone fell it put everyone in crisis; but, that same rope at other decisive times prevented those who fell from sinking because the arms and hearts of the other co-linked held them up. Communities knew that for many things they were all in the same boat. Instead, global financial capitalism has thought to replace this vulnerability of relational trust with algorithms, and in order to increase the grain of a few has forgotten the grain of all.

The Marsia register shows the last signature of the parish priest, Don Giovanni Paoletti, on June 16, 1862. In fact, a few weeks later, on August 25, the new Kingdom of Italy with the Rattazzi Law on Pious Works (No. 753) would transfer the management of the Mounts from the parishes to the new municipality. The Rattazzi Law established The Congregations of Charity, "composed of a President and four members in the municipalities" (Art. 27). In fact, on August 31 a new accounting began in that ancient register, now signed by the president of the "congregation of charity'. Previously the responsibility lay with the parish, the parish priest and two mayors, now the four mountebanks had to follow the at least 14 mountebanks of the commune - previously there were 28 mayors, plus 14 parish priests. Subsidiarity, local trust, was lost, and a few years later there would be no trace of the Mounties, although the social-economic situation was the same as in previous decades, and perhaps worse.

Many pages of these ancient registers moved me, but some deeply moved me. They are those, numerous, where Pastor Paoletti wrote: "Sign of the Cross of Felice Michetti; Sign of the Cross of Stefano Bufagna; Sign of the Cross of Francesco Livi" (18.10.1860). Those mayors, chosen from among the best citizens, were illiterate, so they signed documents with the only signature they knew: the cross: "At the catechism exam Don Serafino asked me to explain to him the sign of the cross. 'It reminds us of the passion of our Lord,' I replied, 'and it is also the way of signing of the unfortunate'" (Ignazio Silone, The Secret of Luke). Illiterate, certainly, but perhaps not unhappy, perhaps no more unhappy than those of us with master's and doctoral degrees. In those crosses I saw again those of my grandmothers and the many old men of my childhood; and then coming out of the archives I read those names and surnames in those of their grandchildren listed on the Monument to the Fallen of World War I that stands in front of the town hall. They could neither write nor read, but they knew how to administer grain for the good of all, because they knew the language of the soul, of pain, of life. What about us? Let's count the research, let's involve so many others./continue